How wearables can protect healthcare workers

Since its emergence, SARS-CoV-2 — the virus that causes COVID-19, has become a global health threat, with more than 23 million cases documented worldwide, and over 821,000 deaths as of August 26, 2020 [1].

With ongoing community transmission from asymptomatic individuals, the current disease burden is expected to rise, as well as the need for healthcare workers in patient-facing roles [2].

The many unknowns about the virulence, spread, and nature of the novel coronavirus bring to the forefront the need for protecting the physical and psychological well-being of healthcare personnel.

This is where advanced wearable technology and AI can step in to keep healthcare workers safe, not just from COVID-19, but also from other physical and mental health threats that can surface as a result of the demanding nature of their work.

Preventing COVID-19 transmission

Due to the personal exposure to patients with SARS-CoV-2 and fellow staff, healthcare workers are at high risk of infection. In an analysis of information from the U.K. and U.S., frontline health care workers had a nearly 12-times higher risk of testing positive for COVID-19 compared with individuals in the general community [3]. This can compromise their own health and may also contribute to nosocomial spread within hospitals. Nosocomial infections are infections that develop as a result of a stay in hospital or are produced by microorganisms and viruses acquired during hospitalization.

Measures to prevent transmission of viral respiratory diseases [4] to and among healthcare personnel generally include:

- PPE (personal protective equipment): Guidelines from the UK and the U.S. recommend mask use for healthcare workers caring for people with COVID-19. However, global shortages of masks, respirators, face shields, and gowns, caused by surging demand and supply chain disruptions, have led to efforts to conserve PPE through extended use or reuse, and disinfection protocols have been developed, for which scientific consensus on best practice is scarce [2, 5].

- Vaccination: In the case of COVID-19, there are no vaccines yet proven to protect the body against this disease.

- Antiviral medications: There are no drugs or other therapeutics presently approved by the FDA to prevent COVID-19.

According to a recent study, weekly screening of healthcare workers using PCR or point-of-care tests for infection irrespective of symptoms is estimated to reduce their contribution to transmission by 25-33%, on top of reductions achieved by self-isolation following symptoms [6].

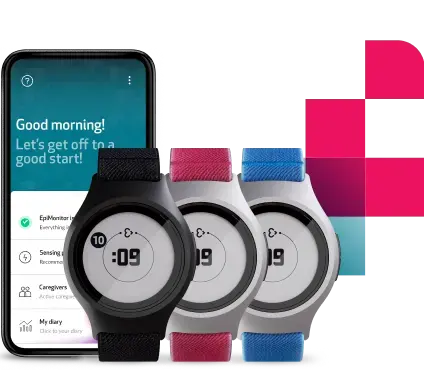

The recent advancements in wearable technology and AI can also offer valuable support in limiting the transmission of the pathogen. Wearable Health Monitoring systems, like the newly released Empatica Care platform, are able to continuously obtain the physiological data of healthcare workers through sensor technologies. The data most commonly collected are pulse rate and pulse rate variability, respiratory rate, oxygen volume in blood or pulse oximetry, signals from the nervous system, peripheral temperature, levels of activity, and rest. These vital signs are recorded unobtrusively via wearable sensors designed to be worn comfortably 24/7, without interfering with the daily tasks of healthcare workers.

The continuous vital signs monitoring of healthcare personnel can help to remotely identify early warning signs of infection. This can enable them to know when to self-isolate, containing the spread and maintaining a healthier workforce. Moreover, with the help of custom digital biomarkers, an algorithm might even be able to detect if someone has a high likelihood of being infected.

Maintaining mental well-being

The well-being of the healthcare workforce is the cornerstone of every well-functioning healthcare system [7]: their mental health needs must be addressed with the same priority of their physical health.

The major causes of psychological distress among healthcare workers include excessive workloads, long working hours, sleep disturbances, and debilitating fatigue. As a result of the pandemic, medical healthcare workers are under an enormous amount of workload pressure that could lead to exhaustion. Doctors who keep working despite experiencing signs of burnout are at risk of depression, reduced productivity, and reduced quality of care [8-9].

How can health monitoring using wearables protect the well-being of physicians?

- Cognitive overload recognition. The nature of treating multiple patients requires physicians to sustain their focus and mental effort for extended periods: their ability to manage mental resources and mitigate the effects of cognitive overload is critical to patient safety. Prolonged cognitive effort activates a sympathetic nervous system response that helps a person to perform at their optimal level [10]. A new study has shown how changes in physiological state as a result of cognitive load can be detected in clinical settings using unobtrusive wearables without hindering the workflow of the wearer [11].

- Sleep tracking and depression recognition. Researchers in China conducted a cross-sectional study involving 1257 healthcare workers during the coronavirus pandemic and reported that 50.4% had symptoms of depression, and 34.0% reported insomnia. It has long been known that sleep disturbances are an important characteristic of depression. Assessment of sleep patterns is often limited by subjective self-ratings of sleep quality. Objective measures, such as sleep regularity measured by accelerometer data with wearable sensors, may provide a more accurate understanding of the subject’s sleep [12] and serve as a diagnostic criterion for depressive disorders.

- Stress detection. Several published studies have demonstrated wearable sensors’ potential to provide individualized, objective correlates of stress [13]. Wearable devices like the E4 wristband are able to collect physiological changes indicative of sympathetic nervous system activity (such as pulse rate, electrodermal activity, skin temperature, electromyography, and accelerometry) and correlate them with emotional state. Most recently, researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School managed to characterize digital biomarkers of stress as detected by the E4 wristband among Emergency Medicine physicians [14].

The detection of stress via wearable sensors could be used to facilitate just-in-time interventions, workplace and process improvements, producing meaningful change that directly reduces physician stress, improve job satisfaction, work productivity, career longevity, and patient care. - Increased efficiency in care delivery and reduced workload. By monitoring patients’ vital signs remotely, healthcare workers can provide precise and timely care, reducing unnecessary patient visits, speeding patient discharge, and reducing avoidable readmissions and emergency department overuse. They can optimize their time attending to patients being in a critically-ill condition. Moreover, those healthcare workers that have been quarantined at home after exposure to COVID-19 can feel empowered by being able to still conduct their duties and monitor their patients’ vitals and assist them remotely.

If you are interested in joining the growing numbers of clinicians and researchers adopting Empatica Care for the remote health monitoring of your patients, workforce, research subjects, or local community, contact our team here or send any questions directly to care@empatica.com. You can also visit Empatica.com/care to learn more.

Sources:

1. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7273299/

3. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.29.20084111v6

4. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13027/preventing-transmission-of-pandemic-influenza-and-other-viral-respiratory-diseases

5. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1535676020919932

6. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/mrc-gida/2020-04-23-COVID19-Report-16.pdf

7. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1386653220300871

8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6262585/

9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30001832/

10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3113724/

11. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0747563220301461

12. https://www.media.mit.edu/publications/objective-vs-subjective-reports-of-sleep-quality-in-major-depressive-disorder-a-pilot-study/

13. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.00093.pdf

14. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/64198

We do not guarantee that EpiMonitor will detect every single seizure and deliver alerts accordingly. It is not meant to substitute your current seizure monitoring practices, but rather to serve as a supplement in expediting first-response time.